Design Pulse

Partners in Design:

Alfred H. Barr Jr. and

Philip Johnson

In a time when Modernism is safely de rigueur—its dictums taught, its champions lionized—it can be tempting overlook the iconoclasm that defined the movement at its outset, not to mention the uphill battle its advocates faced in convincing the public of the promise of cold-rolled steel when Art Deco ornament was au courant. Partners In Design: Alfred H. Barr Jr. and Philip Johnson—on view at Grey Art Gallery until December 9th, 2017—considers the legacy of two such individuals, who tied themselves to the mast of Bauhaus functionalism. Furniture, photographs, and industrial and graphic design comprise the more than 100 objects that populate the exhibition, including pieces from Knoll’s early catalogue: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Barclona Chair, Marcel Breuer’s Cesca Chair, Pierre Jeanneret’s Scissor Chair, and Jens Risom’s 666 Side Chair. The exhibition documents the catalyzing effect of Barr and Johnson had on modern design in America as they sought to present a new architectural lexicon, which they termed the International Style.

Of the exhibition’s two protagonists, Barr was a college art history professor teaching modern art, before he was tapped to be MoMA’s first director. Johnson was a well-to-do Harvard graduate with no formalized architectural training, whom Barr tasked with leading the museum’s newly formed architecture department. The young, impressionable directors were just 27 and the 23 at the time. Johnson, while inexperienced, was infatuated with the industrial-style furnishings coming out of Dessau, Germany, then home to the Bauhaus school. At Barr’s behest, Johnson traveled across the Atlantic to tour the country’s modernist facades, shorn of adornment, with Henry-Russell Hitchcock, who introduced Johnson to the Bauhaus’s towering figureheads: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius. Rather than settling for a piece of the pie, Johnson sought wholesale importation of the style, and only succeeded when the stirrings of war forced its visionaries to seek political asylum in America.

Relics of that trip and others that followed form a significant portion of the exhibition, donated to the museum by Alfred H. Barr and his estate, and supported with ancillary pieces pulled from Grey Gallery’s own archive, including works by László Moholy-Nagy. Guests are encouraged to browse through the exhibitions complete catalog on a Knoll-produced Barcelona Daybed, while a 1960 Barcelona Chair stands nearby on an elevated gallery plinth.

Situated near the site of one of MoMA’s first major modernist exhibitions, Grey Gallery proves itself a unique vantage point from which to revisit the legacy of the Johnson and Barr. The exhibition can’t help but cast Johnson and Barr as the “taste-makers,” “influencers,” and “disruptors” of their time. Such oblique, modern-day resonances help contextualize the importance of Johnson and Barr, who used their own homes as test sites for architects to experiment with new ideas on interior design. Aided by their natural media-savvy, the two willingly turned cameras on themselves as a means of expounding upon their ideas and exporting their tastes. Their apartments served as de facto showrooms, whose aim was to not so much to sell as to convert a skeptical public.

As The New York Times notes in its review of the exhibition, Barr was the more financially encumbered of two, and turned to the Midwestern-born designer Donald Deskey—the designer responsible for Tide’s bulls-eye and Crest’s iconic toothpaste packaging—for stylistically-influenced Bauhaus furniture: “He ordered up a suite of tables and chairs, made with steel tubular armatures and a plastic laminate surface, from a furniture catalog from Ypsilanti, Mich.”

Compared to Johnson, Barr seems to have gravitated toward the pragmatic values espoused by modernism. After receiving a telegram from Johnson reporting that Joseph and Anni Albers utilized round-bottomed flasks as wine decanters, Barr quickly took up the practice himself.

Johnson, on the other hand, is revealed to be Mies’s unabiding pupil and committed aesthete. With money inherited from his prosperous father, Johnson granted Mies and his invaluable collaborator Lily Reich their first U.S.-based commission. His Reich-designed Southgate complex, located at 424 E. 52nd Street, appears as an early forerunner to his own Mies-influenced Glass House, which Johnson completed in New Canaan in 1949.

For the show’s curator, David Hanks, viewing these proximate spaces inevitably leads one to compare and contrast: “Johnson’s spare Mies apartment had no art, while Barr’s was designed for his personal art collection. Johnson’s Mies apartment was done relatively quickly, while Barr’s was created over a period of years.”

Yet the focus of the exhibition rightly remains on what brought the two together: a commitment to advancing modern design. Both Barr and Johnson made a point of dining together once a week to do so, and, according to Hanks, such documented kinship provided the seed for the exhibition: “When we discovered that the Johnson and Barr apartments were in the same building, a floor apart, the comparison of the two interiors and the story of the personal and professional relationship of the partners [became] compelling.”

In addition to focusing on Barr’s and Johnson’s intertwined histories, the show is loosely organized around a reappraisal of two landmark exhibitions—Modern Architecture: International Exhibition and Machine Art—co-developed by Alfred Barr and Philip Johnson during their joint tenure at the Museum of Modern Art. The former is mostly relegated to wall text, with a single model of Gropius’s Bauhaus school reproduced near the museum’s entrance, while the latter is partially recreated to scale.

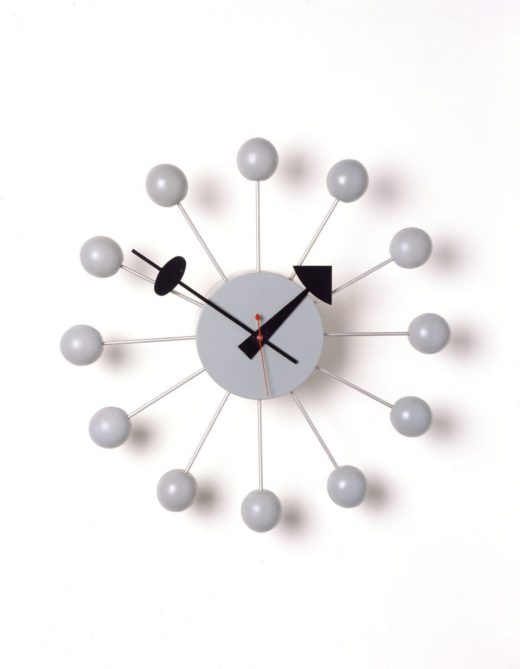

This re-staging of Machine Art emerges as a highlight of the exhibition. In it, Johnson and Barr’s celebrated curatorial instincts are exercised on the most unremarkable of objects: calipers, cake pans, ball bearings, even a kitchen sink. Yet the allure of these everyday items casts a generous light on the most lauded examples of modern design—like Marcel Breuer’s steel and laminate furniture shown in the adjoining room—reminding visitors of modernists’ more humble aim: to create practical, simple, and livable domestic environments as enabled by the developments of modern technology.

In this context, one can see how a transparent Erlenmeyer flask relates to glass-top table, how a bicycle handle gives way to the bent tubular steel of Breuer’s Cesca chair, or how the base of an Electro-chef Stove remains indebted to the regal arc of Mies’ iconic Barcelona Chair. Such correspondence does these icons of modernism a great service, reiterating at once their underlying utilitarian nature and fastidious formalism.

Partners in Design opened September 7th, 2017 and will be on view until December 9th, 2017 at New York University’s Grey Gallery, 100 Washington Square E, New York, NY 10003.